The condition known as ‘exceptional success’ has a deep and complex pathology. It is a form of cultural delusion that encourages the British people to believe only in the best of all possible outcomes – from Brexit to Covid-19, nothing else could ever be allowed. The Golden Disc, an early teensploitation movie set in the London coffee-bar scene of the late 1950s, is the perfect emblem for exceptional success. Walter Benjamin would have understood.

I

In these great times yet to come, a young woman in a formal gown is singing and dancing onstage. Her name is Joan, and she is performing at the start of a movie. Joan is the headline act of the evening. She sings a romantic ballad of dreams and longing, but no one is really listening. The stage is draped with heavy curtains and decorated with vases and baskets of thinly arranged flowers. A grand piano has been set up behind Joan, but no one is playing. A sparse audience of teenagers make out with each other in the upper balcony, flick distractedly through newspapers or quite simply leave. The movie is called The Golden Disc and was originally released in 1958. It’s a Butcher’s Film presentation made at Walton Studios in Surrey, which is just outside London. The movie was a starring vehicle intended to introduce Terry Dene, England’s own version of Elvis Presley, to a wider audience.

II

Like a lot of early rock n’ roll singers and pop stars, Terry got his start singing at the 2i’s coffee bar in Soho. And like a lot of early rock n’ roll singers and pop stars, the industry had no idea what to do with him. Terry Dene’s big break came in 1957 when he played to 5,000 wrestling fans during an interval in the World Championship at the Royal Albert Hall. Next came a TV appearance and a contract with a big record label. What kind of sense did any of this make? At the time Elvis was already on his way into the United States Army and active duty in West Germany. The kids in the coffee bars would soon be moving on to the next wild new craze. Might as well make a movie while you still have the opportunity. Show the world that you’re not the novelty that rock n’ roll will prove itself to be. This is a fable of exceptional success. It’s all about winning – being number one. It’s about selling a million records. The teenage thing can’t last, and there’s no money in coffee. Making a movie, even a low-budget one for an outfit like Butcher’s Film Productions, shows the world that you have range – that you’re a real entertainer. A cheap piece of exploitation cinema, The Golden Disc subverts its fictionalized account of Terry Dene’s rise to stardom by allowing it to take place in world where failure is an absolute impossibility.

III

Prior to going onstage, Joan looks out of her dressing-room window and sees a swarm of teenage fans politely mobbing one of the male singers on the bill. He was seen performing over The Golden Disc’s opening credits before an audience of teenagers packed in tight, seated rows, grinning and heaving with hormonal pleasure. His name is Denis, and he sings about protecting his love from the rain by wrapping her in cellophane. ‘Or maybe you’ll be seen in the latest polythene,’ he croons. His fans look on adoringly.

IV

Secure at first food and clothing,

and the kingdom of God will come to you of itself.

Hegel, 1807

Founded during the Boer War by William Butcher, a chemist from London’s Blackheath, Butcher’s Film Services specialized in the production and distribution of fiercely patriotic movies aimed at working-class audiences in the industrial heartlands of the United Kingdom. Output increased considerably over the course of World War One and World War Two, allowing Butcher’s Film Services to survive in a domestic market that had become increasingly overrun by American products. Walton Studios, where The Golden Disc was made, had started out under the direction of Cecil Hepworth, an early specialist in trick photography. Early Hepworth movies included How It Feels to Be Run Over, Explosion of a Motor Car, both made in 1900, and the first ever film adaptation of Alice in Wonderland in 1903. Following Hepworth’s bankruptcy in 1923, his entire collection of 20,000 original negatives was melted down in order to extract the silver content from them.

V

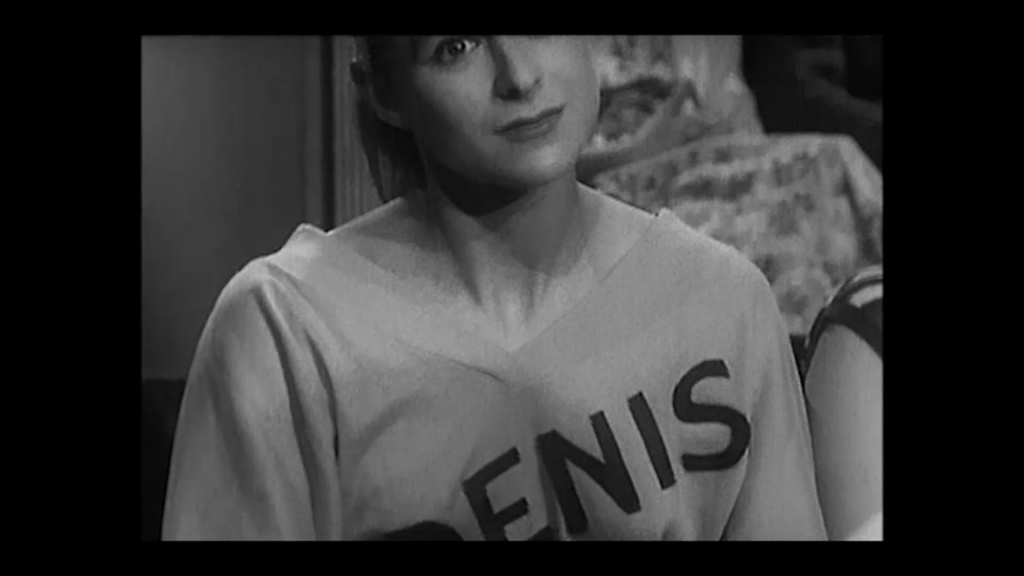

Denis sings to his besotted fans. Teenage girls wear white sweaters with his name on them in large block capitals. It’s their way of making a statement. Entertainment is the complicit function of a culture derived entirely from the deregulated exchange of signs. Every teenager in the audience knows this. There is something strange about the way Denis spells his name, though. As they sway in time to his song, the large letters on the girls’ sweaters appear to be spelling out the word ‘PENIS’.

VI

Not enough has been – or indeed can be – written about Richard Lindner’s 1954 painting ‘Boy With Machine’, reproduced as the frontispiece to The Anti-Oedipus. Guattari and Deleuze hardly seem to mention it at all. Watched from above by Joan at her dressing-room window, Denis tries to make his way from the stage door to his car. One of the young female fans with DENIS on her sweater grabs hold of his neck and doesn’t let go until she sees the disgusted look on his face. Releasing him, she meekly steps aside. Half-hidden by his car door, Denis presents her with a large folded piece of white cloth that is either a handkerchief or a pair of his underpants – it’s really hard to tell. The crowd screams. Exceptional success runs on the prurient energy of complex social machinery. The Golden Disc is filled with mechanical devices constructed precisely in order to distract and channel that energy. The desire for exceptional success, both on an individual and national level, is an expression of suppressed libidinal forces. Richard Lindner, a German painter born and raised in Nuremberg, specialized in highly eroticized renderings of pinball machines and jukeboxes: the most visibly mechanized teenage playthings of the twentieth century.

VII

Think of the darkness and the great cold

In this valley, which resounds with misery.

Brecht, Threepenny Opera

These are hardly new ideas – and yet The Golden Disc, in its dated and cheap splendour, manages to reconfigure them into a radical statement for these great times of Covid and Brexit. ‘Unzip me would you?’ Joan politely asks Terry Dene before adding: ‘How’s singing lessons going?’ Another mechanism springs into life. Terry works backstage at the theatre and dreams of becoming a star. ‘At least you topped the bill,’ he tells her. ‘I don’t suppose I ever will.’ That is all the backstory Terry gets in this movie; like most of its characters, he is friendless and parentless. The closest anyone has to a relative is Joan, who is visited in her dressing room by an Aunt Sarah. There is also a young guy called Harry who once played piano as part of a musical act with Joan. No further details are offered. Harry brings her some flowers. There are hints that Harry and Joan are the children of famous music hall performers – it’s all pretty sketchy. Aunt Sarah has just bought a café near the theatre. ‘The Lucky Charm,’ Joan remarks upon seeing the sign outside. ‘Sounds gay.’ It isn’t. Aunt Sarah’s café is a grim slice of British post-war austerity. The wallpaper is the liveliest thing in the whole place, and even that looks tired. Tables draped in check tablecloths stand in dark rows, and all the chairs are empty. All but one, that is: balding and dour, dressed in an shabby dark suit, identified in the closing credits simply as ‘Morose Man’, Aunt Sarah’s sole customer stares gloomily ahead of him. The café windows are hung with net curtains: a lingering sign of British respectability. Sandwiches and buns have been blandly arranged in glass display stands along the counter. The back wall is decorated with advertisements for OK sauce and CAPSTAN cigarettes, where a woman smiles provocatively, wisps of smoke gently caressing the side of her face. A small blackboard hanging from the wall bears the message: ‘Lucky Charm Café PARTIES CATERED FOR’. Aunt Sarah serves her coffee from a large metal urn ‘Two boys came in the other night and asked for espressos,’ she explains. ‘I thought they wanted newspapers.’ The Morose Man sits in gloomy silence.

VIII

At the end of all our nostalgic dreams, this is what we secretly wish would return to us. The lure of darkness is its very familiarity. ‘The place could be a goldmine!’ Laura raves to Aunt Sarah about her café, but only if she changes everything in it. The opening of Soho’s Moka Bar in 1953 brought ‘continental’ colour to UK’s post-war twilight. By the time The Golden Disc was released five years later, the Soho coffee bar scene had established itself as a significant mid-century fold in the modernist aesthetic. The espresso machine became emblematic of an internationalist style that was capable of operating on a local level, opening up bright new spaces in seedy old neighbourhoods. ‘We could show your aunt what a real coffee bar looks like,’ Harry enthuses.

IX

My wing is ready to fly

I would rather turn back

For had I stayed mortal time

I would have had little luck.

Gerhard Scholem, Angelic Greetings

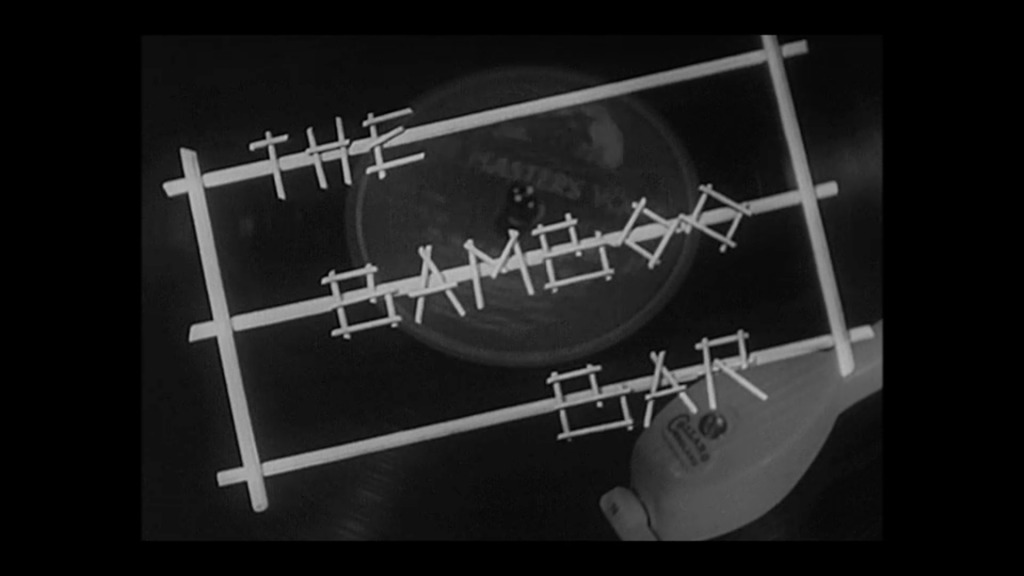

By 1957 there were already 500 coffee bars in London alone, 200 of them serving espresso. Formica table-tops, curved plywood counters, bright laminated plastic, Pyrex cups and vinyl flooring provided open-plan stages and sightlines for entrances and exits, music and dancing; ‘their slinky, snaky continentalism is sliding into the British way of life,’ warned one contemporary observer, as libidinal teenage machines were set running in every city. A brief sequence shows Joan, Harry and Aunt Sarah going from one coffee bar to another: The Tangier, The Bamboo Bar, Bar Minuit Club, The Mocambo, The Black and White, El Dorado… The same song follows Joan, Harry and Aunt Sarah every place they go – as soon as the needle drops on ‘Dynamo’ by Les Hobeaux, the kids start wriggling, shaking and clapping. ‘When you said you love me so, something occurred to the dynamo…’ Could a song ever be so appropriate? ‘What have you done to the dynamo in my heart?’ A girl with a ponytail dances by, apparently sucking Coca Cola through a paper straw from an empty bottle.

X

Every morning the parakeets start shrieking at each other across the courtyard – flashes of green in the corner of a grey sky. The local rose-ringed parakeet population has grown rapidly over lockdown, spreading across South West London. They make such a distinctive sound, and they always seem to congregate in large numbers, so their shrill squawking and trilling echoes and tumbles over itself. Opened a window for some air and heard their calls again. Leaned out to get a closer look, and there they were: occupying a small tree just below me. There were enough green leaves among the yellow to camouflage them, but the bright red of their beaks still stood out. Stood and watched them, barely daring to breathe – counted about six or seven hopping from branch to branch – occasionally one would take flight rising from one level and circling back to another, exposing the delicate colouring on the backs of their spread wings.

XI

Meanwhile, back at the Lucky Charm the Morose Man remains hunched glumly over his solitary mug of coffee. It’s after closing time, and the café is empty, chairs neatly stacked on top of tables: a recurring sight during these great days of Brexit and Covid. The Morose Man makes a great show of slowly finishing his coffee then putting away his chair. ‘There’s nothing to stop you,’ Harry tells Aunt Sarah. ‘You can turn the Lucky Charm into a coffee bar tomorrow.’ Joan agrees. ‘It’ll make a packet,’ she says. ‘Can we have a jerk box?’ Aunt Sarah asks. ‘I guess that’s the first thing I have to order,’ Harry replies. A successful coffee bar is an assemblage of interconnected engines designed to regulate the flow of desires. Working at its heart to their own libidinal rhythms are the espresso machine and the jukebox – and Aunt Sarah can afford both, even if she can’t always get their names right. At this point things really start to get silly. The Morose Man is seen pushing a button on the Lucky Charm’s newly purchased Multi Horn High Fidelity player; then he stands aside while Aunt Sarah’s dingy old café is transformed into a swinging new coffee bar over the course of a single dance routine. Terry Dene ‘the boy from the theatre’ joins in with the heavily choreographed lifting, helping to install a gleaming Gaggia in its rightful place on the counter. ‘Well, we did it,’ says Harry, surveying all the changes they’ve made. ‘Everything we said,’ Joan agrees. ‘Mad line drawings, lucky charms everywhere…high stools…espresso, even music.’ The bar is an instant success – the kids love it. Teenagers rush in and start jiving between the bright Formica table tops before the place is even open. The Gaggia busily generates steam and concentrated shots of caffeine. Exceptional success is a form of sublime ignorance: a state of repressed psychic turmoil that is often mistaken for confidence. Terry Dene quits his job in the theatre to help Harry and Joan wait tables. Everything about the Lucky Charm is transformed – except for the Morose Man, still sitting dejectedly alone, drinking his coffee. Business is brisk. ‘You should be able to get the costs of your alterations back in a couple of months,’ Harry predicts. Then one evening the jerk box gets stuck and needs a mechanic. The kids all start to leave; but Terry pulls out his guitar and wows them into staying. They sway from side to side staring at him in delight. Terry does one song: ‘C’min and be Loved’. It’s not all that great, vaguely recalling Elvis Presley’s ‘All Shook Up’, and we never get to see what happens immediately afterwards.

XII

We need history, but we need it differently from the spoiled lazy-bones

in the garden of knowledge.

Nietzsche, On the Use and Abuse of History for Life

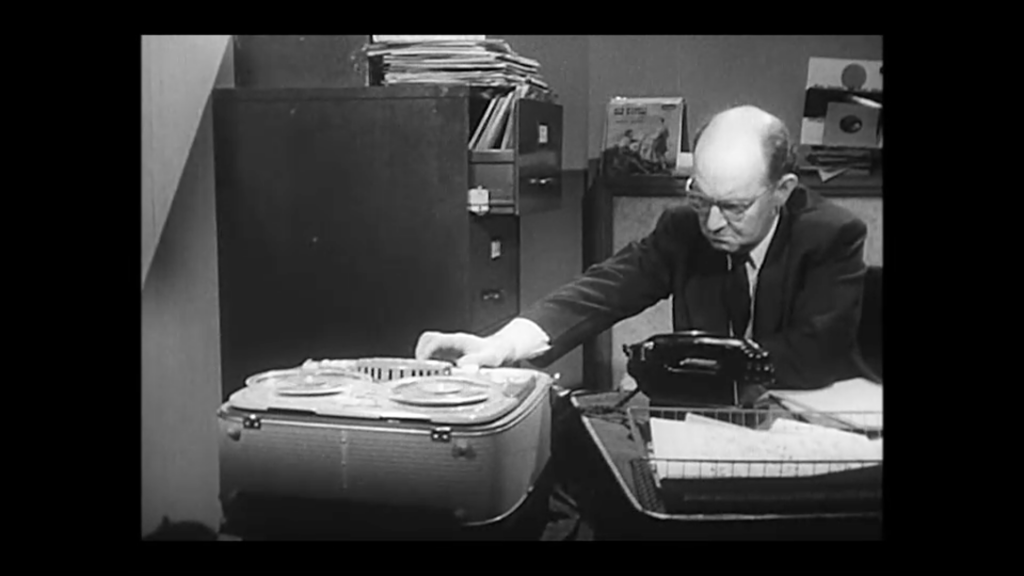

Success turns The Golden Disc into a government-sponsored training film. ‘Just one hit record can sell as many as half a million copies in this country alone,’ Harry informs Aunt Sarah after counting the takings from the Lucky Charm’s jerk box. ‘Altogether, about 70 million discs are sold every year,’ Joan adds. The impact of Brexit and Covid upon the UK music industry has yet to be calculated. ‘Why should they listen to our records then go somewhere else to buy them?’ Aunt Sarah asks. She proposes turning the Lucky Charm into a combined coffee and record bar. No sooner said than done. An old storeroom is emptied, redecorated and equipped with headphones, turntables and other sound equipment. ‘Terry, would you like to demonstrate the tape recorder?’ Joan suggests. ‘Plugged in? Switched on?’ Terry responds before singing to it, backed by music playing on a radio, while a young kid holds out the microphone with an unsteady arm.

XIII

Yet every day our cause becomes clearer and the people more clever.

Josef Dietzgen, Social Democratic Philosophy

Harry and Joan use the tape recorder to promote their old act, schlepping the machine from one dismal record company office to another. ‘You’re just not with it,’ an ageing man in a suit and spectacles explains politely but dismissively. We never hear any of the music they make together, but that’s really not the point. The kids are here for Terry Dene, not Harry and Joan. The Golden Disc came out just as Terry’s career was going into a rapid decline. A star at seventeen, Dene did not handle the experience well. The UK media carried stories of public drunkenness, of Terry smashing shop windows and ripping a payphone off the wall. He loudly proclaimed his undying love for the pop singer Edna Savage, whom he later married and then quickly divorced. Much had been made of Dene joining the British Army to do his National Service; but he was immediately invalided out again after two weeks, the constant bullying having caused him acute mental distress. The media campaign against Dene only increased after this.

XIV

Origin is the end

Karl Kraus, Worte in Versen I

Nothing ever goes wrong for very long in The Golden Disc. Failure only exists as a minor irritation: the grain of sand at the centre of every pearl. ‘Why not make your own records, and let the public judge?’ Aunt Sally suggests to Harry. ‘You knew what the teenagers wanted in the coffee bar, and you know the kind of records to order for them in the shop.’ They call their label Charm Records and set up office on the floor above. ‘We’ve got the talent,’ Harry says. ‘There’s Joanie, and there’s Terry. He could be a big hit.’ Aunt Sarah will talk to the bank, while Joan does the publicity and Harry takes care of the music. ‘A chance at last to do things the way we want to,’ he says clenching his fist and flexing his forearm.

XV

Following the combined coffee bar and record bar, the Charm label is another runaway success – and it is perhaps at this point that The Golden Disc ceases to be entirely credible. The ‘talent’ Harry books and produces is less than thrilling, padding out the last two-thirds of the movie with acts you’ve either never heard of or will ever want to hear again. Each performs in the recording studio under Frank’s personal supervision. Sheila Buxton sings a prim ballad about teenage angst, while Sonny Stewart and His Skiffle Kings perform a rocking little number about wanting to die. Surrounded by unenthused session musicians in V-neck sweaters, Terry Dene records Charm Number One: a bland piece of sing-along pop called ‘Candy Floss’. ‘You’re with me and love must be our boss,’ he cheerfully dictates. A studio clock counts off the minutes and the seconds.

Qui le croirait! on dit,

qu’irrités contre l’heure

De nouveaux Josués

au pied de chaque tour,

Tiraient sur les cadrans

pour arrêter le jour.

XVI

If Charm One offers nothing new, the same goes for Charm Number Two: an instrumental performed by a jazz group referred to simply as ‘the jazz group’. It includes Phil Seaman, one of the finest drummers in Europe at the time and a massive heroin user. Seamen looks pretty out of it in this sequence, a lit cigarette hanging from a thin mouth set in a pale face. The sound quality is terrible: the signal so compressed, it’s almost unlistenable. The studio console is a dark cluster of dials and switches, the recording engineer looking on impassively.

XVII

Undaunted by details, The Golden Disc continues its educational role, teaching teen audiences how to make it in the music industry. ‘Nice going, Terry,’ Harry enthuses after a successful recording session. ‘We made that almost as fast as I’d hoped we would.’ And how is Charm’s search for fresh young talent going? ‘Better than I’d hoped for…five good acts,’ Harry reveals. ‘I’ve got Terry’s contract here.’ Exceptional success always turns out to be better than expected. Trumpeter Murray Campbell belts out the soporific ‘Balmoral Melody’ backed by a string arrangement aimed at a much older audience; meanwhile Nancy Whiskey sings of lost hearts and handsome travellers to a busy skiffle beat – there’s even some lonesome whistling towards the end. An accomplished folk singer, Whiskey later confessed that she hated skiffle – the recording engineer turns a couple of dials on his control panel over the song’s closing fade. Nothing can stop Charm’s rise to the top, however; a montage of front-page headlines, always a sign of rapid change, charts the label’s ascent. ‘Press, TV, the lot!’ Joan enthuses. ‘The orders from the shops are promising too, Aunt Sarah,’ Harry adds. ‘Good orders for Terry’s disc and not too bad for all the others.’ Waiting patiently for his first release to ship, Terry dusts the tape recorder in the Lucky Charm. ‘The coffee bar and the record bar are doing very nicely,’ remarks Aunt Sarah, ‘but we can’t use their profits for this.’

XVIII

At the time of writing, there are upwards of 50,000 parakeets in the UK with the number still rising and most of the population concentrated around London. Ecological conflict spreads across the nation’s capital, taking over parks, gardens and public squares. The local biodiversity starts to mutate. Brightly coloured and exotic, the rose-ringed parakeets become characters in a dystopian science-fiction narrative. Wood pigeons, jays and wagtails start to disappear. Crows and seagulls fight over the garbage being hauled by barge along the south bank of the River Thames.

(Addendum)

A

As is so often the case with exceptional success, The Golden Disc tells a story that was over before it even started. After seeing him sing on TV, the kids in the Lucky Charm recognize Terry Dene even though none of them can remember his name or the title of his latest record. Things become even more confusing when Charm Records release a second Terry Dene disc exactly one week after the first. It quickly sells over a million copies, earning Dene a coveted ‘golden disc’, which is presented to him in the record bar, while the Morose Man, a running joke without a punch-line, continues to brood silently over his coffee.

B

There are further plot complications when a large established record company tries to take advantage of the younger upstart label, and Harry unknowingly confesses his love for Joan to the Lucky Charm tape recorder. Exceptional success has already overcome such moments, however: this is why it can only be understood in libidinal terms, which is to say as some kind of prurient machine. Lust in this film is a simple mechanism that allows everything to turn out well because no one can imagine any other possible outcome. Terry Dene had a couple of real hits, but neither of them sold a million copies; and jazz drummer Phil Seaman died after a prolonged period of heavy drug and alcohol abuse. Meanwhile the government is considering plans to reduce Britain’s parakeet population by killing off some of them.